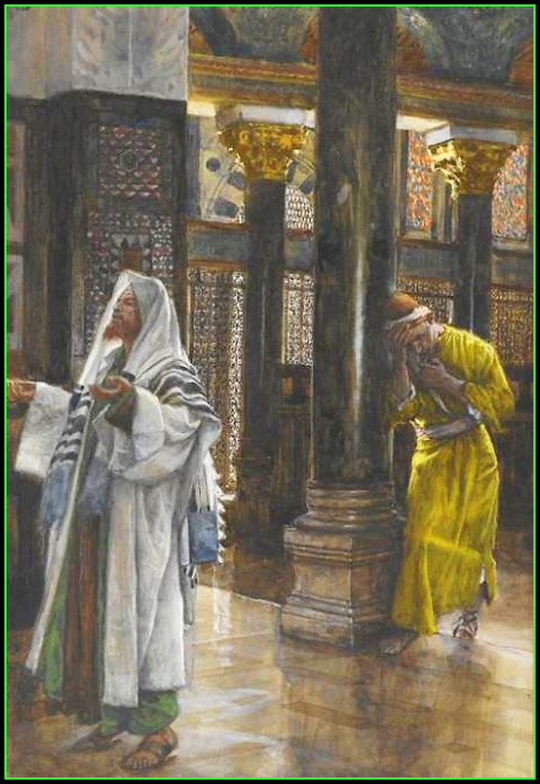

Pharisee and the Publican

Reflection:

The Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector

(Luke 18.1-8)

Some 25 years ago, during my "ACPO" or "Advisory Committee on Postulants for Ordination" retreat, I was asked, "What heresy of the past I felt most afflicted the Church today?"

I feared this might be a trick question—but after some reflection I responded, “Donatism.”

Now most of you are asking: what is Donatism?

Bear with me in a little history (I am an historian after all).

Donatism affected the church in North Africa in the 4th century, when the Roman Emperor Diocletian persecuted Christians.

During the persecution, any Christians who renounced their faith, made offerings to the Roman gods, and turned over any sacred scriptures they had, were spared. Those who refused—especially those caught with Christian texts—were usually killed. While many Christians resisted and were martyred, many others did not. They renounced Christianity, allowed their books to be burned, and were spared.

Now, fast forward a little bit. The persecutions died down with Diocletian’s successor, Constantine. It got a whole lot easier for Christians. Many of those who had denied their faith, returned to the church.

This upset those survivors of the persecution who had remained true to their faith. People were especially upset when those clergy (who had renounced their faith) returned to the church and resumed functioning as priests and bishops. Many Christians in North Africa did not want to allow these lapsed clergy to return.

The issue split the church.

The Bishop of Carthage, Donatus, argued that it would be an insult to the memories of those who had the courage to become martyrs to permit these clergy who had renounced their faith to resume their roles. Indeed, he declared that any sacraments they had administered, or any teaching they had given before the persecution were invalid.

Donatus and his followers wanted a pure church, led by pure clergy, composed of pure members.

Those who disagreed with Donatus responded by arguing that lapsed clergy could be restored to full authority after they performed appropriate penance.

They based this on the concept that Christ offered forgiveness to all and that the holiness of the church is not based on the purity of its leaders or members since all are sinners and have fallen short of the glory of God. The holiness of the church, they argued, rests entirely upon the holiness of God, who in graciousness forgives us our sins in Jesus Christ.

This became the orthodox Christian position. Donatism was declared a heresy.

Donatists, both ancient and modern, are people worried that the impurity, moral failings, and erroneous beliefs of others (or better, what they perceive to be the impurity, moral failings, and erroneous beliefs of others) will somehow corrupt and infect them.

It’s kind of like a child’s notion that we can catch cooties from someone who is a well-known and notorious cootie monster.

We seem to live in a world and a culture abounding in Donatists and Donatism. So many seem to be concerned with their ideological purity, their moral purity, their theological purity, their you-name-it purity these days.

This modern day Donatism affects people of all stripes. There are liberal Donatists and there are conservative Donatists. The incivility of our public discourse is a manifestation of modern-day Donatism. People treat others with whom they differ not just as folks who they think are wrong, but as cootie monsters to be shunned.

Of course, this heresy of the past abounds in the church of the present.

How easily we get into the habit of labelling and judging those who hold different views and positions from our own. You know: those wacko Progressive Christians, those reactionary Evangelicals, those crazy Charismatics, those conservative Catholics, those wishy-washy Liberals.

Sadly, these labels get used not just descriptively, but as a way of drawing lines between the pure and the impure, the righteous and the unrighteous, the holy and the godless.

Name a hot-button issue, and you will find a group of people claiming that unless you agree with them you are corrupting the faith and the church.

Either you should leave, or they will — in search of a purer, more doctrinally correct, more liturgically current, more politically correct, more you-name-it correct church.

Today’s Gospel reminds us that Jesus had to deal with similar tendencies in his day.

Some Pharisees complained, “Why does the teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?” The Pharisees thought that Jesus and his followers would somehow catch cooties by associating with “those kind of folk.”

Jesus responded by telling the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector. Today, we could substitute any modern day Donatist for the Pharisee and whomever he or she regards with contempt as the tax collector.

And so, we find two men, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector, praying in the temple.

The Pharisee stands by himself, and he really is quite impressive. He is a man 'at home' in the temple. He says his prayers. He gives more than he has to. He stands in the correct posture for prayer in the temple, arms raised, and head lifted. He basically gives God a progress report: as far as he can tell, he’s got it all under control, and he’s happy about it. "God,” he says, “I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, unrighteous folks, adulterers, or even like that tax collector over there.”

Meanwhile, standing off in the distance, is the tax collector. He has nothing to show for himself, and he knows it. He earned his living by working for a foreign government collecting burdensome taxes from his own people to support an oppressive regime and to line his own pockets. He’s a crook, a traitor, and a lowlife. He is guilty and he knows it. And so, he keeps his head lowered as he comes into the temple, and begins to pray, full of remorse, beating his breast, and saying, “God be merciful to me a sinner.”

The surprise ending of the story is that the Pharisee, who gives a wonderful performance in the temple, goes home empty. He came asking nothing of God and he goes home getting nothing from God. The tax collector, the despicable fellow that he is, shows up empty-handed, asking for God’s mercy, and goes home justified, that is, in right relationship with God.

Donatists always go home empty. They are so sure of their holiness and purity that they foolishly think they do not need anything from God, certainly not forgiveness and mercy. The only thing they might ask God is to keep the tax collectors, those they believe to be impure, at a safe distance so they do not get infected.

But paradoxically, it is the tax collector, the sinner, who goes home full.

All of us have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. When we come into God’s presence — not trying to puff ourselves up by putting others down — but with an honest and humble acknowledgement of our emptiness, God fills us with love and forgiveness.

The Church’s answer to our Donatism (then and always) is the good news of God’s love for us in Jesus Christ.

None of us, none of us is worthy or deserving of God’s grace and mercy. We have all sinned and none of our political correctness, ideological purity, theological correction, or love of puppies will get us into heaven.

The good news is that while we were yet sinners, God sent his Son Jesus Christ who, through his life, death, and resurrection, has made us acceptable in God’s sight and through his holiness has made us holy and acceptable to him. My purity or goodness, human purity or goodness, has nothing to do with it.

It is all about God’s grace and mercy, freely bestowed on us through the cross of Christ by which we have received forgiveness.

And this is good news indeed! Because we all fall into the Donatist trap from time to time, forgetting that we have no purity or no holiness apart from the grace, love, and mercy of God.

How we respond to this good news ought to make a difference in our lives.

In gratitude for the free gift of God’s grace, we ought to lead better lives, good lives, indeed, holy lives. We ought to be quick to welcome, embrace, forgive, and love — and slow to reject, cast out, judge, or condemn.

All are one in Christ — male and female, rich and poor, black and white, gay and straight, liberal and conservative. All are welcome. All are forgiven. All are loved by God. My purity, your purity, the Church’s purity, has nothing to do with it.

And for that, thanks be to God.

Norman+